INTUSK MAGAZINE

TO THE CORE OF YOUR HEART

The Second Crusade (1147–1149)

February 10, 2023

The Second Crusade (1145–1149) was the second major crusade launched in Europe. The pope and European nobles organized the military campaign to retake Edessa, which had fallen to the Muslim Seljuk Turks in 1144.

Goals of the Crusade

After the First Crusade, three crusader states were established in the east. They were the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Principality of Antioch, and the County of Edessa. Later in 1109, the County of Tripoli was established as the fourth crusade state.

Among them, Edessa was the first state to be established, the most northerly, the least populated, and the weakest.

Edessa fell to Imad ad-Din Zangi (r. 1127–1146 CE), the Muslim independent ruler of Mosul (in Iraq) and Aleppo (in Syria), on 24 December 1144.

Following the capture, which Muslims described as "the victory of victories" (Asbridge, 226), western Christians were killed or sold into slavery while eastern Christians were permitted to remain. A response was called for. The Christians of Edessa had appealed for help, and a general defense of the Latin East, as the Crusader states in the Middle East were collectively known, was required.

The news of the fall of Edessa was brought back to Europe by pilgrims early in 1145 and then by embassies from Antioch, Jerusalem, and Armenia.

After receiving the news from Bishop Hugh of Jabala, Pope Eugene III (1145–1153) formally called for the crusade on December 1, 1145.

The goals of the campaign were stated somewhat vaguely. Neither Edessa nor Zangi was specifically mentioned; rather, it was a broad appeal for the achievements of the First Crusade and Christians and holy relics in the Levant to be protected. This lack of precision would have repercussions later in the Crusaders' choice of military targets.

To boost the Crusade's appeal, Christians who joined were promised a remission of their sins, even if they died on the journey to the Levant. In addition, their property and families would be protected while they were away, and such trivial matters as interest on loans would be suspended or canceled. The appeal, backed by recruitment tours across Europe (notably by Bernard, abbot of Clairvaux), and the widespread public reading of a letter from the Pope (called the Quantum praedecessores after its first two words), was hugely successful, and 60,000 Crusaders made ready for departure.

The Crusade was led by the German king Conrad III (r. 1138–1152) and Louis VII, the king of France (r. 1137–1180). It was the first time that kings had personally led a crusader force. In the early summer of 1147, the army marched across Europe to Constantinople and from there to the Levant, where the French and German troops were joined by Italians, northern Europeans, and more French crusaders who had sailed rather than traveled by land. The Crusaders were reminded of the urgency of military response when Nur al-Din (1146–1174), Zangi's successor after his assassination in September 1146 CE, defeated the Latin leader Josef II's attempt to retake Edessa.

In the spring of 1147, the Pope authorized the expansion of the crusade into the Iberian peninsula and also authorized Alfonso VII of Leon and Castile to equate his campaigns against the moors with the rest of the Second Crusade.

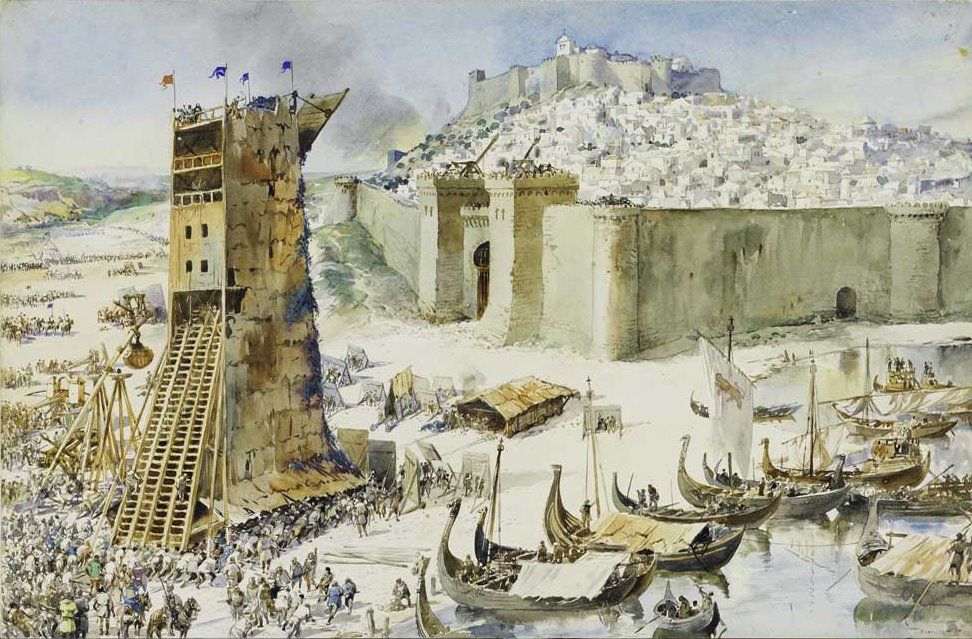

The crusaders agreed to help King Alfonso I of Portugal (1139–1185) attack Lisbon to capture the city from Muslims. With the assistance of the crusaders, the siege of Lisbon began on June 28 1147, and lasted almost four months. With the Moorish rulers agreeing to surrender, the city fell on October 24 1147.

After the victory, crusaders continued the war against the Muslims in the Iberian peninsula capturing Almeria in Spain (17 October 1147) guided by King Alfonso VII of León and Castille ( 1126-1157) and Tortosa in eastern Spain (30 December 1148) after a siege of five months.

Another arena for the Crusades was the Baltic and those areas bordering German territories, which continued to be pagan. The Northern Crusades campaign, conducted by Saxons led by German and Danish nobles and directed against the pagan Wends, provided a new facet to the Crusader movement: active conversion of non-Christians as opposed to liberating territory held by infidels. Between June and September of 1147, Dobin and Malchow (both in modern northeast Germany) were successfully attacked, but the overall campaign fared little better than the usual annual raiding parties sent into the area.

The Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine emperor at the time of the Second Crusade was Manuel I Komnenons (1143–1180). Unlike his predecessors, Manuel seemed greatly attracted to the west. Manuel's primary concern was that the Crusaders were really only after the prized parts of the Byzantine Empire, especially now that Jerusalem was in Christian hands. It was for this reason that Manuel insisted on the Crusade leaders swearing allegiance to him upon their arrival in September and October 1147.

The Byzantines had been attacking Crusader-held Antioch, and the old divisions between the eastern and western churches had not gone away. It was significant that Manuel, despite the diplomacy, strengthened the fortifications of Constantinople.

When the French and German contingents arrived at the Byzantine capital of Constantinople in 1147, things worsened still. Always suspicious of the Eastern Church and now outraged to discover Manuel had signed a truce with the Turks (seen by him as less of a threat than the Crusaders in the short term), the French section of the army wanted to storm Constantinople itself.

The German crusaders had their own problems, with a large number of them being wiped out by a terrible flash flood. The Crusaders were eventually persuaded to hurry on their way east with reports of a large Muslim army preparing to block their path in Asia minor. There they ignored Manuel's advice to stick to the safety of the coast, and so they met disaster.

The German army led by Conrad III was the first to suffer from a lack of planning and not heeding local advice. Unprepared for the harsh semi-arid steppe, the Crusaders lacked food supplies, and Conrad underestimated the time needed to reach his objective.

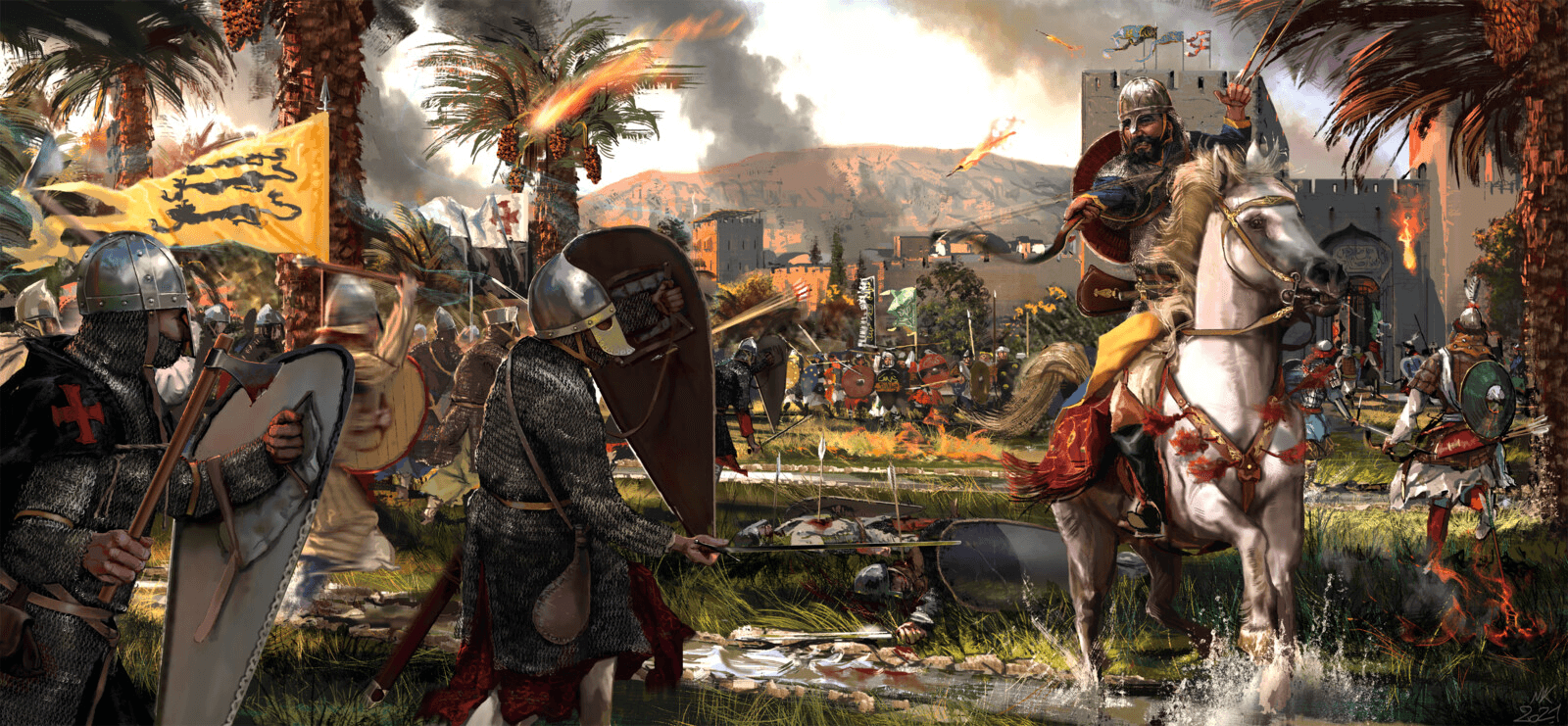

At Dorylaion, a force of Muslim Seljuk Turks, primarily archers, caused havoc with the slow-moving westerners on October 25 1147, and, forced to retreat to Nicaea, Conrad himself was wounded but did eventually make it back to Constantinople.

Louis VII was shocked to hear of the Germans' failure but pressed on and managed to defeat a Seljuk army in December 1147 CE using his superior cavalry. The success was short-lived, though, for on January 7 1148, the French were beaten badly in battle as they crossed the Cadmus Mountains. The Crusader army had become too stretched out, with some units losing contact with each other, and the Seljuks took full advantage.

There were a few minor victories as the Crusaders made their way to the southern coast of Asia Minor, but it was a disastrous opening to a campaign that had not even reached its target of northern Syria.

The Siege of Damascus

Louis VII and his ravaged army finally arrived at Antioch in March 1148 CE. From there, he ignored Raymond of Antioch's proposal to fight in northern Syria and marched on to the south.

In any case, a council of western leaders was convened at Acre, and the target of the Crusade was now selected, not at the already destroyed Edessa but at Muslim-held Damascus, the closest threat to Jerusalem and a prestigious prize.

The Crusader army arrived at Damascus on July 24, 1148, and immediately began a siege.

The defenders had sought help from Saif ad-Din Ghazi I of Mosul and Nur ad-Din of Aleppo, who personally led an attack on the crusader camp.

With Nur ad-Din in the field, it was impossible for the Crusaders to return to their better position. The local crusader lords refused to carry on with the siege, and the three kings had no choice but to abandon the city. First Conrad, then the rest of the army, decided to retreat to Jerusalem on July 28.,

The collapse of the siege after such a short time led some, notably Conrad III, to suspect the defenders had bribed the Christian residents into inaction. Others suspected Byzantine interference.

There was to be no other fight, though, as Conrad III returned to Europe in September 1148 CE, and Louis, after a sightseeing tour of the Holy Land, did the same six months later.

Aftermath

Relations between the Eastern Roman Empire and the French were badly damaged by the Crusade. Louis and other French leaders openly accused Emperor Manuel I of colluding with Turkish attacks on them during the march across Asia Minor.

Nur al-Din continued to consolidate his empire, and he took Antioch on June 29, 1149, after the battle of Inab, beheading its ruler, Raymond of Antioch. Raymond, the Count of Edessa, was captured and imprisoned, and the Latin state of Edessa was eliminated by 1150 CE. Next, Nur ad-Din took over Damascus in 1154 CE, uniting Muslim Syria.

King Amalric I of Jerusalem allied with the Byzantines and participated in a combined invasion of Egypt in 1169, but the expedition ultimately failed.

In 1171, Saladin, the nephew of one of Nur ad-Din's generals, was proclaimed Sultan of Egypt, uniting Egypt and Syria and completely surrounding the Crusader kingdom.

In 1187, Jerusalem capitulated to Saladin. His forces then spread north to capture all but the capital cities of the Crusader States, precipitating the Third Crusade.